This is part three of a four-part series on Father Adrien Rouquette, the poet-priest known as Chahta-Ima.

In 1845, Adrien Rouquette was ordained as a priest by Bishop Antoine Blanc. He quickly became known for his eloquence, delivering a sermon at St. Louis Cathedral that was widely praised. But being a priest in New Orleans did not satisfy him for long.

According to one account, he had a vision, while delivering a sermon, of himself in the woods of Bayou Lacombe, preaching from an outdoor altar. He had a long-standing affection for the Choctaw, and a love of the land, and eventually he asked Bishop Blanc if he could make it his mission to preach to the Indians, and to live among them.

His first dwelling was along Chat-lan-ha (the Indian name for Cane Bayou), close to an Indian burial site. The site was also known as the Nook. The dwelling was converted from an Indian cabin and built on stilts; the combination chapel and cabin was completed in 1847. According to one newspaper description, "the pilgrim saw at one end an altar of plain ornamentation, behind him through the open door was massed the cumulative green depths of the forest. There, he began ministering to the Choctaw and becoming known to them. Initially, they called him the 'Black Robe', for his formal dress".

His mission really took hold when he began to live in the largest Indian settlement in the parish, Buchuwa. Rouquette himself described the site as having "log houses, bark lodges, and shingle-built cabins, with yellow mud chimneys." When he first arrived at Buchuwa, the Choctaw took him to be a government agent, and they were wary of him. He gave them presents of jewelry and cloth, and, with time, they became used to him and accepted him, bringing him the fruits of their hunting, fishing, and farming efforts.

Individual members of the tribe helped him acclimate. Mont-ho-hee, for example, helped him to learn the Choctaw language, while Kan-Ho-Hee served as a translator. By 1859, he had been accepted enough to be invited to their Feast for the Dead. His account of this annual feast is in fact the only recorded description of the rite; it describes a ceremony of lamentations in the woods, followed by a dance and then a banquet at midnight. In reciprocation, Rouquette hosted a feast of his own, making a speech in the Choctaw language which asserted his brotherhood with the tribe. Rouquette was given a lodge in the settlement, and lived with the Choctaw, at times going back to the Nook for greater solitude. Members of the tribe began calling him Chahta-Ima: 'like a Choctaw'.

In 1862, during the Civil War, Buchuwa was burned and pillaged by deserters from both armies. Villagers fled, some of them to the Nook, where Rouquette did his best to take care of them. After the surrender of New Orleans, there was a federal blockade placed on Lake Pontchartrain, making it difficult to get supplies. Rouquette frequently wrote to officers of the Union Army for permission to cross the lake. At one point, he wrote to Admiral Farragut, who supplied him with a federal gunboat as an escort for his trip across the lake. In this way Rouquette was able to maintain a supply of medicine, food, and clothing for the Choctaw at the Nook.

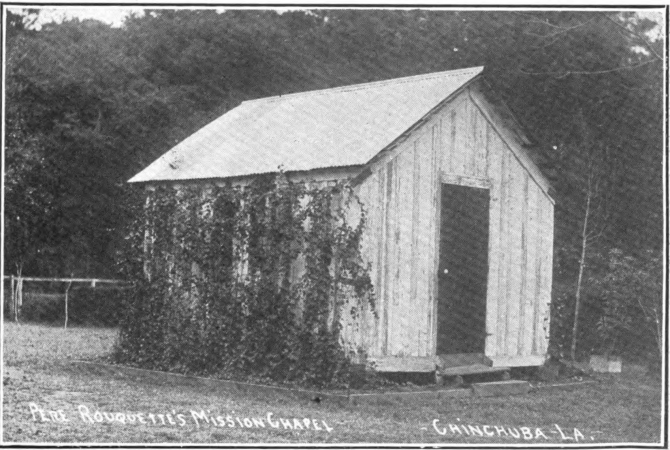

Rouquette's final cabin-chapel was known as Kildara or the "Cabin in the Oak". It was originally a Choctaw long hut, on the bank of Chinchuba Creek. After the sale of the family land, on which the Nook was situated, Kildara became his residence, and his site for his mission work with the Choctaw.

Rouquette's final cabin-chapel was known as Kildara or the "Cabin in the Oak". It was originally a Choctaw long hut, on the bank of Chinchuba Creek. After the sale of the family land, on which the Nook was situated, Kildara became his residence, and his site for his mission work with the Choctaw.

Rouquette's health began to fail him in the 1880s, and he was forced to leave behind his cabin-chapel in the woods, and to live at the Hotel Dieu, in the French Quarter, where he was cared for by nuns. He received visitors there, including members of his Choctaw flock, for the length of his decline. He died on July 15, 1887.

In 1884, he had written "I have done for my Indians all that I could do; I have given them everything; I have eaten of their food; I have slept on the ground; I have lived their life; I have become a real Choctaw; and I wish to die and be buried in the midst of them". In fact, he was to die and be buried in New Orleans, in the clergy tomb in St. Louis No. 2. There wasn't enough time to inform the Choctaw living across the lake, so his funeral was attended by some of the Choctaw living in the city. A group of Choctaw women, barefoot out of respect, walked with the funeral cortege, and one older woman carried a cross made out of herbs.

His respect for and love of the Choctaw shone through in his writings and in letters to his peers. His approach was one of understanding, not cultural conversion; he spoke to them in their own language, even translating the bible into Choctaw for them. He had the highest admiration for them, as quoted in Chahta-Ihma and St. Tammany's Choctaws: "I have lived with them, studied their domestic manners, shared their unrestrained but orderly freedom, and I do say to their praise...they are the true Americans."

Kildara was the last surviving cabin-chapel of Rouquettes'. It was moved onto the grounds of the Chinchuba Deaf-Mute Institute, where it eventually burned. But, luckily, not before his vestments and other artifacts were removed from the cabin, and preserved for future study.

In the final blog post of this series, we will discuss the fate of the oak grove at Kildara, under which Rouquette preached the gospel to the Choctaw.

For more information on Pere Rouquette and his relationship with the Choctaw, Chahta-Ima and St. Tammany's Choctaws, opens a new window is essential reading.

Add a comment to: Spotlight on History: Father Adrien Rouquette, Part Three