Tuberculosis was a scourge of a disease, commonly known as the white plague. By the end of the 19th century, it had killed one in seven people who had ever lived. In 1919, it had an annual death toll of 150,000, and was said to cost the United States 500 million dollars every year. Fifty percent of American children were infected by it before the age of ten, and yet it was not only curable but preventable. As it was a contagious disease, it was discovered that cleanliness and hygiene went a long way towards stopping its spread. Public health officials emphasized the importance of fresh air, sleeping outside, and healthy eating. Tuberculosis camps or sanatoriums sprang up in rural areas around the country, offering a clean, healthy environment in which to get the "fresh air cure" for the disease.

Kate Gordon was a suffragist and civic leader in New Orleans. She advocated for improvements to the sewerage of New Orleans, pushed for Tulane Medical School to accept female students, instituted the use of rubber tires on ambulances in the city, and founded a group for the prevention of cruelty to animals. On the other side of the coin, she, along with her sister Jean, lobbied the state legislature for years to pass a bill mandating the sterilization of the mentally ill. She was best known, though, for her role as president of the Louisiana Anti-Tuberculosis League, and the founder of what would eventually become Camp Hygeia.

Kate Gordon was a suffragist and civic leader in New Orleans. She advocated for improvements to the sewerage of New Orleans, pushed for Tulane Medical School to accept female students, instituted the use of rubber tires on ambulances in the city, and founded a group for the prevention of cruelty to animals. On the other side of the coin, she, along with her sister Jean, lobbied the state legislature for years to pass a bill mandating the sterilization of the mentally ill. She was best known, though, for her role as president of the Louisiana Anti-Tuberculosis League, and the founder of what would eventually become Camp Hygeia.

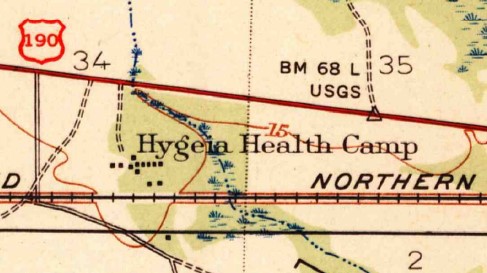

In 1908, Camp Hygeia started out nameless, as 50 acres of pine woods in St. Tammany Parish donated by the Health Home Company for the treatment and isolation of tuberculosis patients. It was initially funded by leftover money from a yellow fever campaign. In 1910, the railroad was moved ten miles from the site of the camp, making it very inconvenient to get to. As a result, the Louisiana Great Northern Railroad donated forty acres next to the new route, and the camp was immediately moved to that acreage, slightly east of Lacombe. Camp Hygeia officially opened in July 1910. It was named after the Greek goddess of health, cleanliness, and hygiene. The Camp eventually constituted a little over 80 acres of pine forest south of Highway 190.

by the Health Home Company for the treatment and isolation of tuberculosis patients. It was initially funded by leftover money from a yellow fever campaign. In 1910, the railroad was moved ten miles from the site of the camp, making it very inconvenient to get to. As a result, the Louisiana Great Northern Railroad donated forty acres next to the new route, and the camp was immediately moved to that acreage, slightly east of Lacombe. Camp Hygeia officially opened in July 1910. It was named after the Greek goddess of health, cleanliness, and hygiene. The Camp eventually constituted a little over 80 acres of pine forest south of Highway 190.

It is important to note that Camp Hygeia did not take in Black patients. And in 1918, when the Louisiana Tuberculosis Commission looked to extend the services of Camp Hygeia to Black patients, the town councils of Covington and Mandeville resolved that this should not be done; rather, a sanatorium should be built for them elsewhere in the state. The St. Tammany Farmer commented on March 9, 1918: "St. Tammany parish people are as cordial and hospitable as can be found anywhere, and they welcomed the sick who have come here for the benefit of its wonderful climate, but it draws the line at being made the dumping ground for negroes afflicted with tuberculosis." As much as Camp Hygeia was a boon to Louisianans sick with the disease, it is important to remember that its benefits were not available to all Louisianans.

White sufferers of tuberculosis would first go to the Anti-Tuberculosis Free Clinic, housed in New Orleans at 1309 Tulane Avenue, to get an examination. If the patient's condition was found to be in the first or second stage, and thus curable, they were sent to Camp Hygeia. Behaviors that might exclude someone from camp were spitting on the ground, and sleeping indoors. For those who were beyond care, the Anti-Tuberculosis League supplied them with “eggs and milk daily,” as well as medicine. The goal was to provide “freedom from worry and cost” to sufferers of tuberculosis.

White sufferers of tuberculosis would first go to the Anti-Tuberculosis Free Clinic, housed in New Orleans at 1309 Tulane Avenue, to get an examination. If the patient's condition was found to be in the first or second stage, and thus curable, they were sent to Camp Hygeia. Behaviors that might exclude someone from camp were spitting on the ground, and sleeping indoors. For those who were beyond care, the Anti-Tuberculosis League supplied them with “eggs and milk daily,” as well as medicine. The goal was to provide “freedom from worry and cost” to sufferers of tuberculosis.

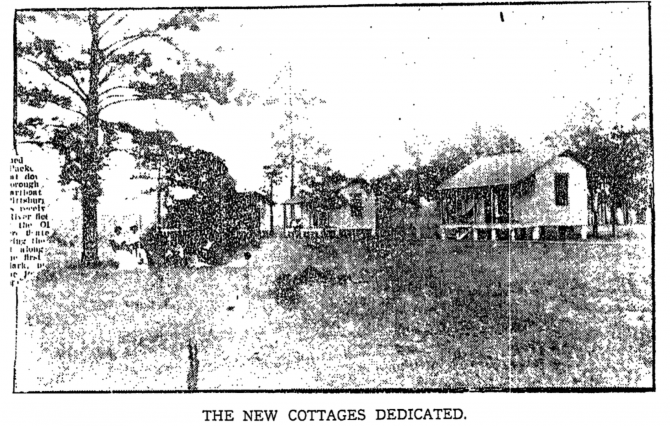

By September 1910, seven cottages had been completed, with an informal dedication on September 19.  The dedication was attended by representatives of the Benevolent Knights of America and the Alden Branch of Sunshiners. They were given a tour of the facilities, including their "modern conveniences" of showers and bathtubs.

The dedication was attended by representatives of the Benevolent Knights of America and the Alden Branch of Sunshiners. They were given a tour of the facilities, including their "modern conveniences" of showers and bathtubs.

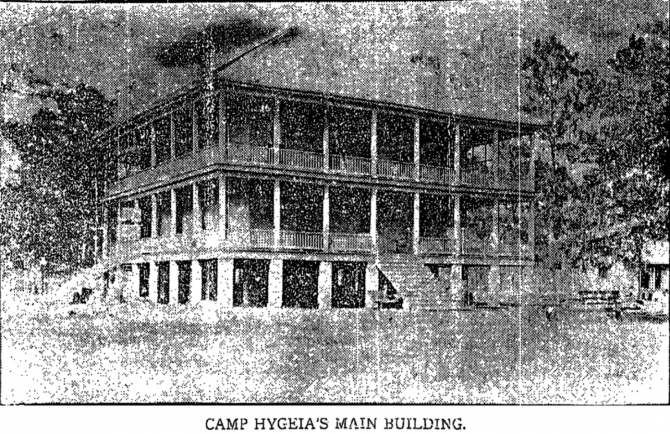

The cottages for men, women, and children were housed in the main building, with balconies arranged for sleeping. Each cottage had two well-ventilated and sunny rooms, along with a porch. There was an artesian well, which provided drinking and bathing water for the camp. They had a former fire department horse named Alfred, who pulled the plow for their fields; a collie named King, a white rabbit, cows, fish in a pond, and chickens.

Their meals were fortifying; in a 1914 example, Sunday dinner consisted “entirely of things that were produced there,” including chickens, eggs, corn, milk, and watermelons. On a daily basis, patients had four meals, and many left the camp both in recovery and having gained weight. One patient, A. Reinhardt, spoke to the dedication visitors and told them, enthusiastically, “Heaven was just like Camp Hygeia.”

For the entire lifespan of Camp Hygeia, the institution was constantly in need of money and charitable support. Many benefits were held for the camp, along with annual Christmas seal sales drives. Seemingly every year, Hygeia put out a plea for Louisianans to support their efforts, and seemingly every year, the fundraising fell short. Camp Hygeia, according to the accounts of the day, seems to be an example of making do with what was available.

For the entire lifespan of Camp Hygeia, the institution was constantly in need of money and charitable support. Many benefits were held for the camp, along with annual Christmas seal sales drives. Seemingly every year, Hygeia put out a plea for Louisianans to support their efforts, and seemingly every year, the fundraising fell short. Camp Hygeia, according to the accounts of the day, seems to be an example of making do with what was available.

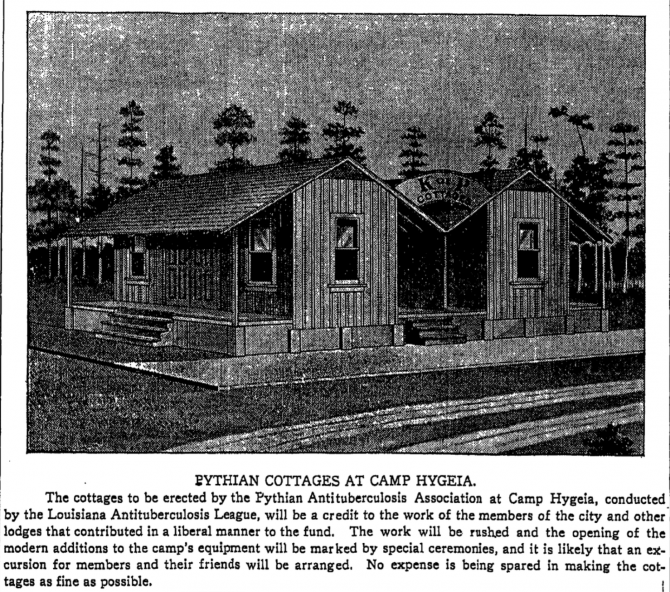

Much of what came to the Camp was via donation. In 1911, the Camp asked for a gift of rocking chairs, so that patients could relax on their porches. Two more cottages were built by the Junior Order of American Mechanics, and its ladies’ auxiliary, Daughters of America. Singer Sewing Machine Company donated two sewing machines, and Isidore Newman donated an electric fan for their office. In 1916, a “handsome” four-seated carriage was donated. Over the years, more organizations built cottages for Camp Hygeia, including the Typographical Union, the Improved Order of Red Men, the Woodmen of the World, and the Pythian Lodge. By 1917, the camp also had a dining-room screened with copper wire, built by the Druids, and a four room double cottage built by the Pythians.

Much of what came to the Camp was via donation. In 1911, the Camp asked for a gift of rocking chairs, so that patients could relax on their porches. Two more cottages were built by the Junior Order of American Mechanics, and its ladies’ auxiliary, Daughters of America. Singer Sewing Machine Company donated two sewing machines, and Isidore Newman donated an electric fan for their office. In 1916, a “handsome” four-seated carriage was donated. Over the years, more organizations built cottages for Camp Hygeia, including the Typographical Union, the Improved Order of Red Men, the Woodmen of the World, and the Pythian Lodge. By 1917, the camp also had a dining-room screened with copper wire, built by the Druids, and a four room double cottage built by the Pythians.

The Camp in the pines served tuberculosis patients for twenty years, after which it became a part of the Orleans Tuberculosis Hospital at 1931 Gentilly Avenue in New Orleans. After Kate Gordon's death, the hospital was familiarly known as "Miss Kate's Hospital". It is said that Camp Hygeia saved 17 men who were able to fight in World War 1, and that it saved 1,430 patients in its two decades of service.

Part 2 of this series will look more closely at Clara Fromherz, the "Angel of Hygeia".

All quotes via the Times-Picayune, accessed through NewsBank.

Add a comment to: Spotlight on History: Healing at Camp Hygeia, Part 1