Éire go, Deo: Ireland is Forever

Happy March! A certain holiday involving lots of green is coming up, so what better time to celebrate Ireland than now?

Ireland began as the northwestern tip of Europe, to which it was adjoined tens of thousands of years ago. The last great ice age left much of Ireland scoured and relatively flat. The earliest confirmed human settlements on Ireland occurred nearly 18,000 years ago by nomadic hunters, although some archaeologists believe that humans could have settled in Ireland millennia earlier; such evidence is impossible to prove due to the effects of glaciation, which would have destroyed virtually any signs of human life. The last ice age ended around roughly 8000 BCE, by which point Ireland was no longer connected to the continent due to rising sea levels (some scientists suggest that Ireland was separated from Britain as early as 14,000 BCE).

Certain studies suggest evidence of human activity reappears as early 11,000 BCE, though the earliest confirmed archaeological records put the arrival of humans at around 7900 BCE, just after the end of the ice age. These humans mainly lived as hunter-gatherers, with no permanent settlements, until about 4000 BCE, when Neolithic settlements begin appearing. The Neolithic Irish mainly lived in coastal settlements; sites indicate the likelihood of experienced shipbuilders and fishermen. The early colonists to Ireland consumed seafood and various tree nuts, in addition to wild game when available.

One of the earliest and most impressive cites of Neolithic Ireland is the monument of Newgrange. Built between 3200-3100 BCE, this massive structure was used for centuries, apparently as a funeral site or tomb, although it fell in decay by 2000 BCE. Although the structure rivaled the Great Pyramids of Giza in terms of age, this site fell into disuse and was gradually forgotten. The earliest mention of Newgrange in modern times did not occur until the mid-12th century.

The Irish Iron Age began around 600 BCE with the arrival of the Celtic culture. Celtic influences and language became predominant and intermingling with the natives formed a new society and much of the basis for the modern Gaelic culture. Gaelic culture dominated the British Isles and also formed the basis of Scots, Brittonic, Welsh, and other local groups.

Within another few hundred years, Britain came in contact with a new group of explorers: the Romans. The Roman Empire dominated most of Europe, geographically and politically. As early as 55 BCE, Julius Caesar led an expedition to Britain, though his visit was short-lived and did not extend to Ireland (then-called Hibernia). Roman forces returned to Britain in 43 A.D., and from there began a gradual conquest of modern-England and parts of Wales. The Roman conquest ended at what became known as Hadrian's Wall, currently located not far from the Scottish border and several miles south of the more northerly and briefly held Antonine Wall. While Roman commanders campaigned across all of Great Britain, no records remain that confirm whether the Romans ever visited Ireland/Hibernia. Aside from a few comments in Tacitus' Agricola, there is very little physical evidence suggesting the Romans ever went across the Irish Sea, even if they did probably consider it.

Myths and Legends of Ancient Britain and Ireland

A Traveller's History of Ireland

While scholars debate whether or not the Roman military ever made it to Ireland, it is without doubt that the Catholic faith did cross the Irish Sea. As time went on, the Roman Empire abandoned pagan worship and gradually turned to Christianity. At some point prior to the 5th Century A.D., the religion appears in Ireland, probably thanks to missionaries from Roman Britain. The two most famous were Palladius and St. Patrick, the latter of whom was famous for 'ridding Ireland of snakes'. The Catholic faith remains the largest Christian denomination in Ireland, and Ireland boasts the largest church attendance in Western Europe.

Ireland thrived during the early Middle Ages. As the Roman Empire collapsed and culture and technology regressed through much of Europe, Ireland maintained a strong, insolar culture. This golden age of Irish culture, united by the Catholic faith and a nominal "high king" came to an end in the 9th century with the arrival of Viking raiders. Much as they had through England and parts of Central Europe, the Vikings pillaged significant portions of Ireland. Though the Vikings did not stay for good and left less of a mark than in England, the Vikings did leave numerous settlements that grew into prosperous towns, including the present-day capitol of Dublin.

In the 12th century, another wave of invasions threatened Ireland, this time from the south. A few decades after the Norman conquest of England, a second conquest stretched out to take over Ireland. Led by Richard "Strongbow", the Norman English took control of a large portion of eastern Ireland, allegedly at the behest of the dispossed King of Leinster. The resulting invasion displaced numerous local lords and established a region known as the Pale, which remained governed by the Normans for the next 400 years. The English king at the time, Henry II, further authorized additional invasions of Irish territory and officially appointed his younger son John (the infamous Prince John) as 'Lord of Ireland.'

Over the next several years, the Norman-English lords gradually intermarried with the local Irish, tolerating their customs and generally turning a blind eye to some of the more insidious demands of subsequent English kings. Another change struck in 1542, when Henry VIII put down a rebellion by the Lord of Kildare and proclaimed himself King of Ireland. Subsequent efforts made by himself and his children (Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I) resulted in plantations full of English and Scotish settlers, disarmament of the local lords and replacing disloyal ones with lords more loyal to the Tudor monarchs, and the introduction of the English law system. Irish culture and language even became illegal in certain areas.

Under the new system, the people of Ireland transitioned into tenant farmers, forced to grow crops for export to England. As sustenance, many of these farmers relied on the potato, a recent acquisition from the New World. The worst times came many years later, in the mid-19th century with the Irish Potato Famine. Thousands of people died, families lost their homes, and entire villages ceased to be. Many Irish people began to immigrate (and many had for years previously), especially to the United States. The United States boasts one of the largest populations of Irish immigants and people of Irish descent; do you have Irish in your ancestry?

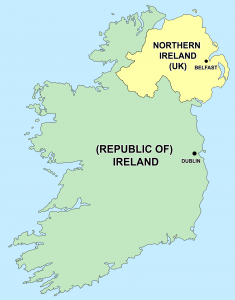

In the late 19th century, momentum began to build for more representation for the people of Ireland. Eventually Ireland won the right to home rule and in 1922 independence. That year, the Republic of Ireland was formed, but the whole of the island did not join this new nation. The six northern provinces elected to remain part of the United Kingdom. Ireland did not participate during the Second World War, although tens of thousands volunteered to serve in the British Army. In the 1960s, conflict arose between Protestants and Catholics, and this started the Troubles, a distressing time of Irish history where many were killed or injured during fighting. The Troubles lasted until mid-1990s, when the two sides agreed to peace, the Republic of Ireland adopted a new constitution, and Northern Ireland was allowed to chose its own fate.

Ireland is today an industrialized and prosperous country. Though it has been through its shares of ups and downs, the Emerald Isle perseveres. People across the world are proud of their Irish heritage.

Looking for something else? As always, the St. Tammany Parish Library is happy to offer free use of our online catalog, opens a new window for more interest on this and other topics. Happy St. Patrick's Day!

Add a comment to: Éire go, Deo: Ireland is Forever